How to Help Someone Who Is Grieving

An anonymous listener wrote in and asked how to help someone who is grieving. She is worried she’ll say the wrong thing, cause her friend more pain, and generally make things worse. She’s not alone—we worry so much about comforting “the right way” that sometimes we don’t do it at all. This week, Savvy Psychologist Dr. Ellen Hendriksen covers four reasons we clam up around grief and how to come out of our shells.

Ellen Hendriksen, PhD

Listen

How to Help Someone Who Is Grieving

It’s uncomfortable. You don’t know what to do. You’re worried you’ll say something stupid. So too often, when a friend or loved one is grieving, we end up saying nothing at all. How to stop feeling awkward and guilty? Here are four of the most common barriers to lending that helping hand plus how to overcome them.

Barrier #1: You don’t know what to say

Feeling tongue-tied is the most common barrier. We don’t know what to say because we feel powerless. We want to fix things or take the pain away, and there are no words in the world that can do that.

A good go-to when you can’t channel your inner Hallmark store is simple, sincere, and conveys three messages: one, this is hard; two, I care about you, and three, I’m here for you.

There are a zillion variations on this theme. For example, you might say, “What you’re going through is awful. I love you. Call me any time day or night.” Or this: “I’m so, so sorry about Don’s passing. You’re so important to our family. How can we help out?” Or simply state the basic recipe: “This is hard, I care about you, I’m here for you.”

And quite honestly, even if you can’t remember the three components and end up mumbling a cliche like “I’m sorry for your loss” or “My sincere condolences,” it’s fine. Those time-honored phrases won’t win any creativity contests, but if they convey your concern and come from the heart, they’re not cliches anymore—they’re support. You can even sit in silence. It’s awkward, but it’s your presence, not your words, that are most important.

Barrier #2: You’re worried you’re intruding

We’re taught to offer privacy and respect after a death. But privacy shouldn’t mean radio silence and it’s never disrespectful to offer your support and love.

And there’s a difference between “not intruding” and withdrawing. So go ahead and talk about the person who died. Remember the person, tell stories, say how much they meant to you. This does two things: first, it shows that what happened isn’t unspeakable—that the loved one’s name isn’t taboo just because she passed away. And second, it simply acknowledges the loss. Even if your stories are light hearted, remembering the person who died shows you’re serious about remembering them. And that is never intrusive.

See Also: How to Cope with Profound Grief: A Interview with Rosalie Lightning Author Tom Hart

Barrier #3: You don’t know how to make them feel better

This barrier is a no-win situation. You’re not going to make them feel better. You’re not going to fix things. But guess what? You don’t have to.

Grief is like a bad meal—the only way through is to digest it.

Actually, many of the stock phrases we use to try to make people feel better, like “He’s in a better place,” or “Things will be back to normal before you know it,” or even “Everything’s going to be all right” are lacking at best, insulting at worst. Who’s to say the best place for the person who died wasn’t alive and at home with her family? And no, things might never be normal or all right again.

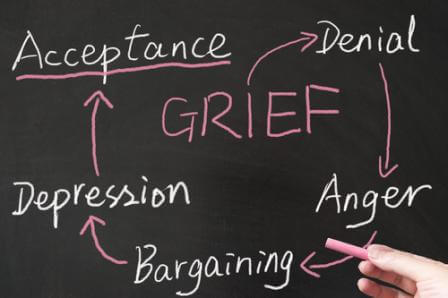

Grief is like a bad meal—the only way through is to digest it. And processing grief takes time—up to a year or two for many people, though you never really ‘get over’ a loss. Their loved one will be missed forever. Indeed, it would be worse if they weren’t missed.

But the urge to make someone feel better is strong. We want to help, to contribute. So instead of offering advice, offer support, whether emotional support or what’s called instrumental support—that is, tangible offerings like making a casserole or driving their kids to school.

There are two schools of thought on this. One is to extend an open-ended offer of help. This gives the bereaved a chance to ask for what she really needs, whether it’s getting stuff done or just providing company. But don’t say, “Just holler if you need anything”—the “if” will kill the chance of them ever reaching out.

The other school of thought is to state what you’d like to do for them—mow the neglected lawn, organize a meal train, or take the kids to the zoo for an afternoon. This takes the burden off of the bereaved to have to generate tasks and manage a support team on top of everything else. If you’re worried the person will feel self-conscious, you can piggyback the task on something you would do anyway: “I just made enough lasagna to feed an army—may I come by and give you some?” Or, “I pick my kids up from school every afternoon; we’d love to give Jordan a ride, too.”

Barrier #4: You don’t do well with this stuff

It hits too close to home, you’re afraid of death yourself, or you’re sure you’ll break down and your loved one will awkwardly end up having to console you. It’s good to be honest with yourself. Too often we think up some other reason to avoid the grieving person when we’re really just afraid we can’t handle their pain.

Ask yourself: what’s the worst-case scenario? Maybe you’re worried you’ll be overcome and sob uncontrollably? You’ll choke up and be unable to speak? Whatever your horror story, ask yourself, “How bad would that really be?” Your loved one might appreciate the honesty of your tears or the depth of your care. Grief ain’t pretty. But it’s not supposed to be. It would actually be weirder if we breezed through it with a wink and a smile.

And what if you screwed up a past chance to support someone who lost a beloved? Well, for better or worse, you have another chance. Anniversaries of the death are often difficult, as are wedding anniversaries or birthdays. Test out a few words of solace next time one of those dates roll around. Your friend will likely be touched you remembered. It’s never too late to show you care.

For more, check out How to Handle Grief and Loss from the archives. I’ll post it to the Savvy Psychologist Facebook page so you can find it there.

For even more, subscribe to the Savvy Psychologist podcast on iTunes or Stitcher, listen on Spotify‘s mobile app, or like my page on Facebook. You can also get the transcript delivered straight to your inbox by signing up for the Savvy Psychologist newsletter.