Today’s topic is whether it’s OK to begin a sentence with and, but, or or. The short answer is yes, and just about all modern grammar books and style guides agree! So who is it that keeps saying it’s wrong to do it?

It’s Fine to Start a Sentence with a Coordinating Conjunction

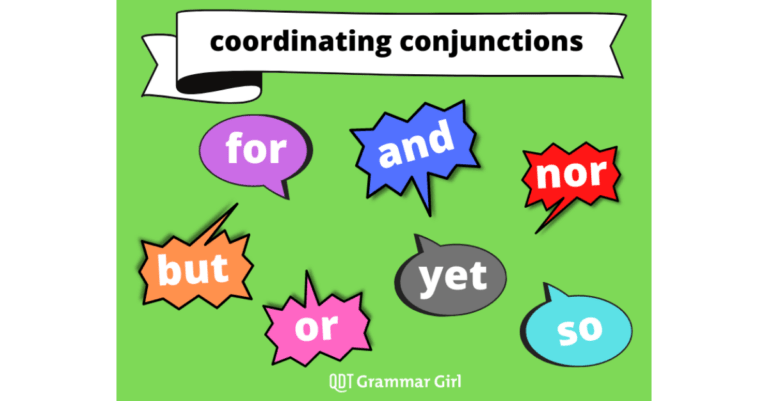

And, but, and or are the three most common members of a group of words known as coordinating conjunctions. The question about whether it’s grammatical to begin a sentence with and, but, or or is actually the question of whether it’s grammatical to begin a sentence with a coordinating conjunction. Here’s what some of the big usage guides say on the matter. The one that seems to get quoted the most is the Chicago Manual of Style, which says:

There is a widespread belief—one with no historical or grammatical foundation—that it is an error to begin a sentence with a conjunction such as and, but or so. In fact, a substantial percentage (often as many as 10 percent) of the sentences in first-rate writing begin with conjunctions. It has been so for centuries, and even the most conservative grammarians have followed this practice.

Both Garner’s Modern American Usage, and Fowler’s Modern English Usage call this belief a superstition. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary of English Usage (or MWDEU) says, “Everybody agrees that it’s all right to begin a sentence with and,” and notes that you can find examples of it all the way back to Old English.

Many People Have Been Taught That It’s Wrong

However, MWDEU also observes that “nearly everybody admits to having been taught at some past time that the practice was wrong.” So where did this idea come from? In The Story of English in 100 Words, David Crystal writes:

During the 19th century, some schoolteachers took against the practice of beginning a sentence with a word like but or and, presumably because they noticed the way young children overused them in their writing.

But instead of gently weaning the children away from overuse, they banned the usage altogether! Generations of children were taught they should ‘never’ begin a sentence with a conjunction. Some still are. (Entry for and)

If you’ve ever been angry at a teacher who kept your whole class in from recess because two or three of your classmates were misbehaving, you should have a big problem with this rationale for not beginning a sentence with a conjunction. They think you can’t handle the freedom of using conjunctions!

It’s true that you can easily fall into a habit of beginning sentences with coordinating conjunctions. Still, being able to do so occasionally allows you more flexibility and control over the tone of your writing, and allows more variety. For example, listen to the following two sentences:

Squiggly turned in his application on time. But he forgot to include his application fee.

By making the clause about turning in the application a single sentence, and beginning the next sentence with but, we have the combination of a sentence-final pause and a sudden afterthought delivered in a short burst. Now suppose we joined the two clauses with a comma:

Squiggly turned in his application on time, but he forgot to include his application fee.

Now there’s not as much of a pause, so the surprise is lessened. If that’s what you want, fine, but if you really want the pause that comes from ending a sentence, what do you do? Another possibility is to begin the second sentence with a transition word or phrase with a similar meaning, such as however, like this:

Squiggly turned in his application on time. However, he forgot to include his application fee.

A Conjunction at the Beginning of a Sentence Creates a Different Feeling

Let’s face it, though: However doesn’t have the same feel as but. It’s a slightly higher register. Furthermore, like all transition words and phrases, it requires a pause afterward, which we write as a comma. [But pauses don’t always equal commas!] It signals that a contrasting thought is on the way, and allows the reader to prepare. If that’s what you want, fine. But if you want that information to hit harder and faster, the conjunction but is a better choice.

Are We Making Sentence Fragments?

Another reason for believing that you cannot begin sentences with a coordinating conjunction is the idea that this turns a sentence into a fragment. This misconception may come from a confusion about what conjunctions are. Conjunctions are traditionally divided into three kinds: coordinating, correlative, and subordinating. It’s only that last kind that will turn a clause into a fragment. In fact, coordinating and correlative conjunctions are different enough from subordinating conjunctions that they should probably not all be called conjunctions, but that’s a topic for another episode.

Coordinating Conjunctions Versus Subordinating Conjunctions

So how can you make sure you’re using a coordinating conjunction and not a subordinating conjunction? The easiest way is just to memorize the coordinating conjunctions. Of course you know about and, but, and or, because they’re the most common and the most versatile. In addition to joining clauses, they can join almost any other kind of word or phrase. Another coordinating conjunction that can join many kinds of words and phrases is yet. In addition to these four, there are a few less-versatile conjunctions that can only join clauses: for, nor, and so. (Actually, if you speak British English, you might also use so to join verbs and verb phrases, but in American English, it sounds funny when you do that.) Many grammar sources, including my book Grammar Girl’s Quick and Dirty Tips for Better Writing, keep track of the coordinating conjunctions by using the mnemonic word fanboys, which stands for for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so. If you listened to episode 366, you may remember that the word slash has been evolving into a coordinating conjunction, too, but that’s still far from entering the list of coordinating conjunctions in Standard English.

Subordinating conjunctions include words such as if, because, although, when, and many others. Unlike coordinating conjunctions, which can make a complete sentence by combining with two clauses or just one clause, subordinating conjunctions definitely need two. For example, because I wasn’t happy is a fragment, because it has combined with only one clause: I wasn’t happy. On the other hand, I switched jobs because I wasn’t happy is a complete sentence, with because joining two clauses: I switched jobs and I wasn’t happy.

One quick and dirty tip for distinguishing subordinating conjunctions from coordinating conjunctions is this: a coordinating conjunction has to come between the clauses it connects, but a subordinating conjunction can come before both of them. For example, you can say, “Because I wasn’t happy, I switched jobs,” with because coming before the first of the two clauses. That means because is a subordinating conjunction. On the other hand, it’s nonsense to say, “But Squiggly forgot to include his application fee. He turned in his application on time.” The but has to come in between the clauses, which tells us that it’s a coordinating conjunction.

So as long as you know how to avoid accidental sentence fragments, feel free to begin sentences with a coordinating conjunction. But don’t overdo it. Or it might be disconcerting to your audience. And we wouldn’t want that, would we?