How Understanding ‘Toy Story’ Can Help You Get into College

Three words that could get you accepted to the University of Chicago: make it new.

Photo by JD Hancock CC 3.0

Here’s a secret: most Disney and Pixar films have the same structure. And it goes a little something like this:

-

Status Quo. As the story begins, life is like this.

-

Inciting Incident. Something happens to disrupt the status quo. (Fun fact: it’s usually 12-15 minutes into the film.) Often, this is when we learn the main character’s “want” (a.k.a. external desire), which is what the character thinks will make him or her happy. In Finding Nemo, for example, Marlon wants to protect his child forever. In The Incredibles, Bob Parr wants to be an amazing superhero.

-

Raising the Stakes. Over the next hour or so, things get more serious and dangerous. Often, this is when we learn that the character has a deeper need (a.k.a. internal desire). In Finding Nemo, Marlon discovers he needs to not protect Nemo, but to let him go. In The Incredibles, Bob Parr needs to learn to be not only an amazing superhero, but an amazing dad.

-

Moment of Truth. Often, this is when the hero must make a huge choice, after which there’s no turning back. Sometimes this involves our hero choosing between his want and need (as in Finding Nemo), and sometimes this choice helps our hero achieve both his want and need (as in The Incredibles).

-

New Status Quo. As the story ends, we see that life is different from when we began.

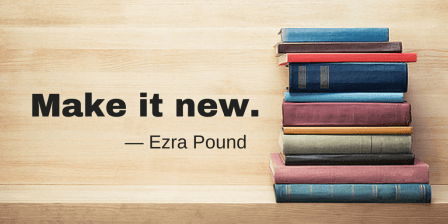

This structure will sound familiar to you if you’re familiar with Joseph Campbell’s monomyth or Hero’s Journey.

Image by Bernard Goldback, CC BY 2.0.

In Campbell’s version, the hero returns with “new knowledge” to share with those who didn’t or couldn’t make the journey.

One name for this is narrative structure and here’s a quick example of how it works in the film Toy Story:

-

Status Quo. Woody and Andy are best friends and Woody is Andy’s favorite toy.

-

Inciting Incident. Buzz Lightyear arrives and Woody is no longer Andy’s favorite toy. Woody gets jealous and his want is to get Buzz out.

-

Raising the Stakes. As the story continues, Woody pursues his want (to get Buzz out) although as an audience we begin to see that Woody has a deeper psychological need—to overcome his jealousy and (to not get Buzz out, but) to let Buzz in.

-

Moment of Truth/Climax. The crazy neighbor kid ties Buzz to a rocket and threatens to blow Buzz to infinity and beyond. Here, Woody must choose between his want (to get Buzz out) and his need (to let Buzz in, to accept him).

-

New Status Quo. Woody chooses to save Buzz, fulfilling his need over his want. In the end, Woody and Buzz and Andy all play nice together.

In a nutshell, that’s narrative structure.

And this structure has become familiar to you through the many films and stories you’ve seen and heard in your life.

But here’s something you probably didn’t know: narrative structure can help get you into college.

How? Well, you must be clever. Like the heroes and heroines of many animated films—you must be brave. And, most importantly, you must find a college that values uncommon thinking.

Kinda like the University of Chicago.

In fact, the University of Chicago values uncommon thinking so much that, for years, it spurned the advances of the Common Application, calling its own application the Uncommon Application. And then, in 2012, the University of Chicago relented and joined the other hundreds of schools on the Common Application. #awkward

Weird past University of Chicago prompts:

-

So where is Waldo, really?

-

Find x.

-

Why are odd numbers odd?

-

How do you feel about Wednesday?

So, what does the narrative structure have to do with getting into college?

Well, over the past several years, some of my smartest students have used narrative structure to write amazing essays that helped get them into the University of Chicago in particular. (It’s important to note that it wasn’t only these essays that got them in—they had wonderful GPAs, test scores, and extracurricular resumes. But their essays helped.)

And here’s the thing: they didn’t just use narrative structure.

Oh no. They did something extra.

Because, let’s face it, every story has pretty much been written, right? (Some argue, in fact, that there are only ten basic story plots.)

What did these students do that was special?

They made it new.

What does it mean to “make it new”?

To make something new is to make the usual seem, well, unusual. Or, conversely, to make the unusual seem usual. Like wearing a duct tape dress to prom, for example. Making garlic ice cream. Or telling the story of a family surviving a tornado—from the perspective of the tornado.

Some films that made it new include Moulin Rouge, which was actually Puccini’s opera La Boheme. Or The Lion King, which was basically Hamlet. And the 1993 film Homeward Bound: the Incredible Journey about the talking dogs and cat was actually… well, the 1963 film Homeward Bound: the Incredible Journey.

Musicians who’ve made it new:

Jay Z’s Izzo (H.O.V.A) → Jackson 5’s I Want You Back

Fugee’s Ready or Not → Enya’s Boadicea

Kanye West’s All Falls Down, Jesus Walks, Through the Wire → all rip-offs–and all on the same album. (Fun fact: As of this writing, Kanye has sampled 414 other songs. Source.)

So how can you make it new?

First, find a story you know really well. Or choose a story that lives in the public consciousness. Cinderella, for example, or Santa Claus.

Then take that story and do something new with it.

Like what? Change the location: put Cinderella in your own school, for example. Or change the perspective: be Cinderella, or better yet be the misunderstood stepsister and tell her story. (Gregory Maguire is an author who, among others, reinterprets fairy tales.) The sky’s the limit here.

But this above all: be sure your essay answers the question “So what?” Why? It will lead you to insight, which is possibly the most important quality an essay (of any kind) can provide its reader. Kati Sweaney (Assistant Dean of Admissions at Reed College) agrees with me, and in conversation last month told me (that’s the College Essay Guy) that she can tell a student is ready for college-level work if that student can answer the question “So what?” So write that question at the top of your essay, in the margins, and at the end.

Want an example of a rad essay that uses narrative structure, makes something new and answers “So what?” Go here where you can read Jacqueline Kwon’s amazing reinterpretation of “Why did the chicken cross the road?” You’ll also find an essay by Christian Lau, who had to answer one question in order to get into the University of Chicago. The question? A simple one: Rock, Paper or Scissors?

Then find out if either of them actually got in.

So here’s a quick re-cap of what we’ve learned so far today:

#1. Essays are like movies, and their structures are there for the stealing. Ahem, borrowing.

#2. But don’t just steal. Do something original. Make it yours. Make it new.

#3. Answer “So what?” in the essay. Then answer it again. Then again. Keep going till you’ve said something original. Something smart. Something you didn’t expect to say.

Then make sure you pack extra mittens.

Because Chicago winters are crazy cold.

Book quotation background image courtesy of Shutterstock.

Ethan Sawyer has been helping students tell their stories for more than ten years and is the author of the Amazon bestseller College Essay Essentials, the #1 book on college essays. He has reached thousands of students and counselors through his webinars and workshops and has become a nationally recognized college essay expert and sought-after speaker. He is a graduate of Northwestern University, received an MFA from UC–Irvine, and is an active member of NACAC, WACAC, SACAC, OACAC, HECA and IECA (feel free to Google those) and lives with his wife and daughter in Los Angeles. For more information, visit www.collegeessayguy.com.