Weird Coordinating Conjunctions: Yet, For, and So

Neal Whitman explains why FANBOYS is a myth and why yet, for, and so are different from and, but, and or.

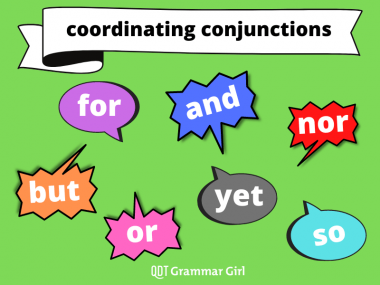

A few episodes back, I was talking about starting sentences with coordinating conjunctions, and I mentioned that one way of remembering the coordinating conjunctions is the word FANBOYS, whose letters can stand for for, and, nor, but, or, yet, and so. However, I kept the focus on the conjunctions and, but, and or, because the other conjunctions are rather different from these three. Well, today, we’re going to look at exactly how different for, nor, yet, and so are.

In this episode, I’ll refer to coordinating conjunctions as coordinators for short, unless I need to compare them to subordinating conjunctions. Now, if the coordinators don’t all behave alike, how did they get lumped together in the first place, and how did the word FANBOYS come to be the canonical mnemonic for remembering them?

Coordinating Conjunctions and the FANBOYS

In a paper titled “The Myth of FANBOYS,” Brett Reynolds writes that his earliest find for the mnemonic is in a 1951 book called Learning to Write. Since then, membership in the class of coordinating conjunctions has to some extent crystallized around the seven that FANBOYS covers, but Reynolds points out that there hasn’t always been agreement. Some of the lists he cites include all the “fanboys” conjunctions plus whereas. Another list leaves out yet and so. Still another list includes a few transition words and phrases, such as however, only, still, therefore, and then.

So what do coordinators have in common? Two things.

First, they can take two words or phrases of the same category, and join them to make a larger word or phrase of that same category.

Second, they need to come between the two items they connect, or if they’re connecting more than two, they need to come right before the last item. Some coordinators can join more categories than others, and some have additional powers, but that’s basically it.

How Typical Coordinating Conjunctions Join Things

Let’s look at the two most typical coordinating conjunctions, and and or. They can join almost any kind of part of speech or phrasal category: Jack and Jill, hot or cold, laughed and shouted, with or without you, over the river and through the woods, eating pizza and drinking beer, shape up or ship out. They can join sequences of categories, too, as in I gave a watch to my father and a necklace to my mother.

How But Is Different

Now let’s look at but. Already, we start to run into differences. For one thing, although but can connect just about any kind of word or phrase that and and or can connect, it can’t connect noun phrases. Although we can say Squiggly and Aardvark and Squiggly or Aardvark, the phrase Squiggly but Aardvark doesn’t work at all. If we partner the but with a not, we can say not Squiggly, but Aardvark, but now we’re talking about correlative conjunctions, not coordinators.

[Note from Neal, added 8/4/2014:

As it turns out, you CAN use but to connect noun phrases:

-

Squiggly ate all of his french fries, but none of his vegetables.

-

I like red wine but green grapes.

-

Three administrators but only one teacher was on the committee.

But is still pickier than and and or in what noun phrases it can coordinate though. The rule I’m inducing is that the contrast has to be overt. Understood contrast in the context is not enough: Even if we might find it surprising that Aardvark and Squiggly both did something when they usually avoid each other, “Squiggly but Aardvark” isn’t improved.]

Another way that but is different from and and or is that we can only use it to join two items, not a series. With and and or, we can have phrases such as The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly, and win, lose, or draw. That’s because and shows addition, and or shows alternatives, and it’s easy to imagine lots of additions to a set, and lots of alternatives. But, on the other hand, shows contrast, and it’s hard to conceive of a contrast between more than two things. We can say slow but steady, but we can’t say slow, careful, but steady.

Yet Is Most Like And, Or, and But

We’ll consider yet next, because it’s the coordinator that’s most like and, or, and but. Yet is like but, because it can join just about any kind of phrase except for a noun phrase. It also shows contrast, as but does, although it’s a stronger kind of contrast known as concession. When you join two things with yet, it’s not just a contrast; it’s a surprising contrast. For example, to describe my complicated, love-hate relationship with something, I might say, “I like it, but I hate it,” or I could highlight the surprising contrast by saying, “I like it, yet I hate it.” When yet joins clauses, it is like the subordinating conjunction although. The sentences I like it, yet I hate it and I like it, although I hate it have the same meaning. However, we know yet is a coordinator, because like other coordinators, yet has to come between the clauses it connects. We can say Although I hate it, I like it, but Yet I hate it, I like it is nonsense.

Even with all these similarities to other coordinators, one big difference separates yet from them: It can combine with other coordinators. Instead of saying “I like it, yet I hate it,” I could say, “I like it, and yet I hate it.” Or “I like it, but yet I hate it.” In this way, yet is more like an adverb than a conjunction, but it still has enough coordinator-like properties that we call it a coordinator.

Nor has enough complications that I’m going to save it for another episode, where I can also talk about neither and not.

The Coordinators For and So Show Causation

The coordinators for and so show causation, which is probably why the only kind of phrases they can connect are entire clauses, unless you speak British English, in which case so can also join verb phrases. For has the same meaning as because, but we know it’s a coordinating conjunction because it has to come between the clauses it connects. For example, we could say She was starving, for she hadn’t eaten since the earthquake, but we can’t say For she hadn’t eaten since the earthquake, she was starving.

So is an interesting case. It can show the effect of a cause, as in She hadn’t eaten since the earthquake, so she was starving. Like other coordinators, it has to come between the clauses. It’s ungrammatical to say So she was starving, she hadn’t eaten since the earthquake. But listen to this sentence that I spoke during the sponsor message at the beginning of this episode: So they’ll know I sent you, use the URL AudiblePodcast.com/GG. Did you hear that? I used so at the beginning of the first clause, instead of between the two clauses it connected! Does that mean it’s a subordinating conjunction after all?

Not exactly. Notice that in So they’ll know I sent you, the word so isn’t showing an actual effect. It’s showing an intended effect, or in other words, a purpose. When so shows purpose, it acts like a subordinating conjunction. So which is it, a coordinating conjunction or a subordinating conjunction? One solution would be to say that so is actually a pair of homonyms, one of them a coordinating conjunction and the other a subordinating conjunction. That’s kind of a cop-out, though. On the other hand, it’s cognitively irritating to have so as a coordinator that violates one of our main criteria for coordinators.

Traditional grammar books divide all words into eight nice and neat parts of speech, and our subconscious expectation is that any words that are the same part of speech should be able to do exactly the same kinds of things. The truth is that instead of being like mailboxes in a post office, parts of speech are more like splotches of paint on an artist’s palette. Although it’s easy enough to count how many splotches there are, the edges are blurry, and some tend to run into each other. Nowhere is that clearer than with the small family of words known as coordinating conjunctions.

This podcast was written by Neal Whitman, who has a PhD in linguistics, blogs at LiteralMinded.wordpress.com, and is a regular contributor to the online resource Visual Thesaurus.

Sources

Reynolds, Brett. “The Myth of FANBOYS.” 2011. TESL Canada Journal/Revue TESL du Canada 105.29, 104-112. https://www.teslcanadajournal.ca/index.php/tesl/article/view/1092/911